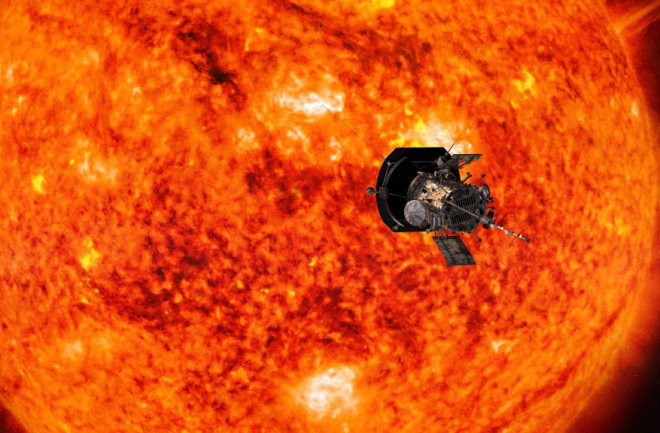

The Parker Solar Probe will help explain the mysteries of our sun's atmosphere - a mission first envisioned more than half a century ago. (Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins APL/Steve Gribben) We often equate light with a lack of mystery. We elucidate or illuminate answers. So it’s tad ironic that the brightest object in our solar system remains one of its most mysterious. Scientists still don’t understand why the sun’s corona, or atmosphere, is hotter than its surface — or why the solar wind accelerates as it races away. We have theories: Nearly invisible nanoflares blow out heat. Waves of electrically conductive, fluid-like plasma transfer energy to other twisting waves, creating eddies that dump heat into the corona. Magnetic field lines collide and snap in new directions, propelling heat outward like atomic bombs. And waves of protons, called ion cyclotron waves, snake around the sun's magnetic field, heating and accelerating the solar wind. If you polled solar scientists, they’d probably say we have most of the picture, says David DeVorkin, a space historian at the National Air and Space Museum. However, it needs validation. “There is nothing as valuable as in-situ measurements — if you survive the in-situ measurements,” he says. That’s where NASA’s Parker Solar Probe comes in. It’ll fly closer to Dante’s inferno than we’ve ever gone. But Parker’s full measure rests not only its potential to solve a defining astronomical mystery, but also in its history. The spacecraft will soon become NASA’s oldest successfully-launched mission proposal. It emerged during the very culture wars and power struggles that built and defined NASA.

NASA’s 60-Year Race to Touch The Sun

Newsletter

Sign up for our email newsletter for the latest science news

0 free articles left

Want More? Get unlimited access for as low as $1.99/month

Stay Curious

Sign up for our weekly newsletter and unlock one more article for free.

View our Privacy Policy

Want more?

Keep reading for as low as $1.99!

Already a subscriber?

Find my Subscription

More From Discover

Recommendations From Our Store

Shop Now

Stay Curious

Subscribe

To The Magazine

Save up to 40% off the cover price when you subscribe to Discover magazine.

Copyright © 2023 Kalmbach Media Co.